Waterbird movements

Dynamically responding to environmental change

Most people are familiar with the concept of wildlife ‘migration’, loosely defined as the seasonal movement of animals from one region to another. Many animals move regularly with the seasons to find food, avoid the cold weather months and/or move to areas that are good for breeding but only accessible for part of the year.

However, the movements of waterbirds around Australia’s interior are more complex and have largely been a mystery. Many of Australia’s inland waterbirds depend on important wetland sites being flooded for breeding. However, Australia’s interior environments are naturally subject to highly variable and often unpredictable weather. Rainfall and therefore river flow and wetland availability can vary dramatically from year to year. In recent years, water extraction and climate change have made wetland availability even more uncertain.

Without tracking bird movements directly, it is difficult to say for certain which movement strategies different species and individuals are using to handle this uncertainty, for example:

(a) Residency – which includes ‘sedentary movements’, ‘central-place movements’, and ‘commuting’, where individuals remain in one area or home range (including while breeding), usually returning to particular locations between relatively short-distance foraging trips, or display territoriality.

(b) Nomadism – which includes ‘facultative migration’ and ‘facultative movements’ where individuals move varying distances and directions irregularly and are generally responding opportunistically to resource availability. It can also include ‘fugitive movements’ that occur in response to disruption or disturbance of resources, individuals or flocks.

(c) Migration – this is sometimes called ‘obligatory migration’ or ‘seasonal migration’, where individuals regularly move relatively long distances predictably between set locations and in set directions, usually seasonally or annually.

Knowing which strategies species and individuals are using, including where, when, and how they move, helps us to know where, when and how to support their populations with management. Below, we discuss some of the movement strategies we’ve seen during our tracking work.

On the move! An adult straw-necked ibis in flight.

Flexibility is key

Australia’s inland aggregate-nesting waterbirds encompass about a dozen species including Pelecaniformes (cormorants & pelicans) and Ciconiiformes (egrets, herons, ibis, spoonbills) that breed in colonies that range in size from hundreds to hundreds of thousands of individuals.

Some of their most important breeding sites depend on extensive flooding to provide suitable habitat and food for chicks and their parents. These sites and the areas around them need our support to ensure that enough habitat and food is available for long enough to ensure that chicks survive.

Between breeding events, these species need plentiful feeding habitats and food to grow and survive – so after leaving the breeding site, they move around the landscape looking for the best feeding spots.

Prior to satellite tracking, we had poor knowledge about where and when these birds travelled before, during and after breeding events. We didn’t know what routes they took, whether they all behaved the same ways or differently, or whether juveniles and adults moved to the same places.

Our team has been tracking waterbirds from this group of species since 2016, with some individuals tracked continuously for more than five years including from their natal site (that is, the nest where they were born) through to their first breeding attempt as an adult.

This rich dataset of tracked movements has given us new insights into the movement of Australia’s inland waterbirds. It shows that flexibility is key – these species use mixed and flexible movement strategies, with many individuals able to switch between strategies over time, doing different things in different years or seasons. To cope with Australia’s dynamic environment the movements of Australia’s inland waterbirds are themselves very dynamic.

Let’s take a closer look at the three main movement strategies used at different times by Australia’s amazing inland waterbirds and see what they look like when we have satellite tracking data available to illustrate movements.

Residency

Waterbirds sometimes travel hundreds of kilometres, roaming huge areas of the Australian continent (see examples below). At other times, however, they have periods of residency.

Residency is common during the breeding season, when waterbirds take turns tending to the nest and flying to different parts of the landscape to find and bring back food. But waterbirds also sometimes undertake periods of residency outside the breeding season. For example, they may “overwinter” in one particular locality, taking advantage of good resources and weather.

An Australian white ibis on its nest. Nesting periods are one time during the year when waterbirds have periods of ‘residency’, but it may not be the only time!

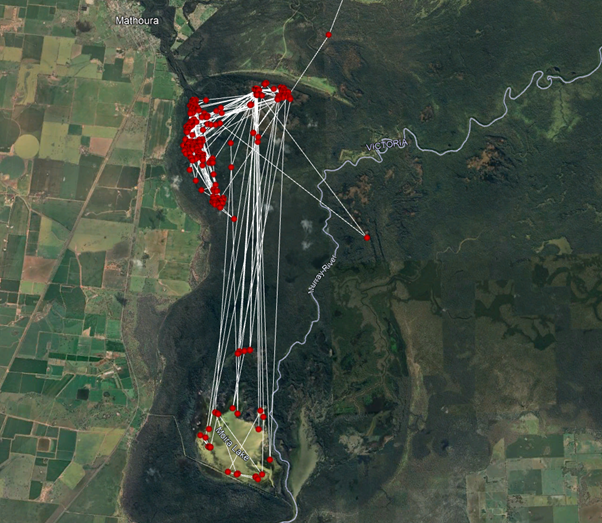

The below map shows an example of what waterbird movements can look like during periods of residency, with many satellite fixes clustered in a small area and frequent trips from a central location (often a nesting site) to a foraging area.

Movements of Elvis the royal spoonbill during a period of ‘residency’ at Barmah-Millewa Forest. This individual remained in one general area, returning to particular locations between relatively short-distance foraging trips (in this case, foraging trips from the northern part of Barmah-Millewa south to Moira Lake are clearly visible).

Nomadism

The idea of a ‘nomad’ is well-known from human culture. We generally understand nomads either as communities that move from place to place as a way of obtaining food or finding pasture for livestock animals, or as individual people who choose not to remain settled in any one particular place for their lives.

It turns out that many Australian inland waterbirds are also nomads! An interesting thing is that within a given species (for example straw-necked ibis), some individuals may be nomadic while others might be resident or migratory (even over the same time period). Equally, the same individual bird may be nomadic in some years but not in others.

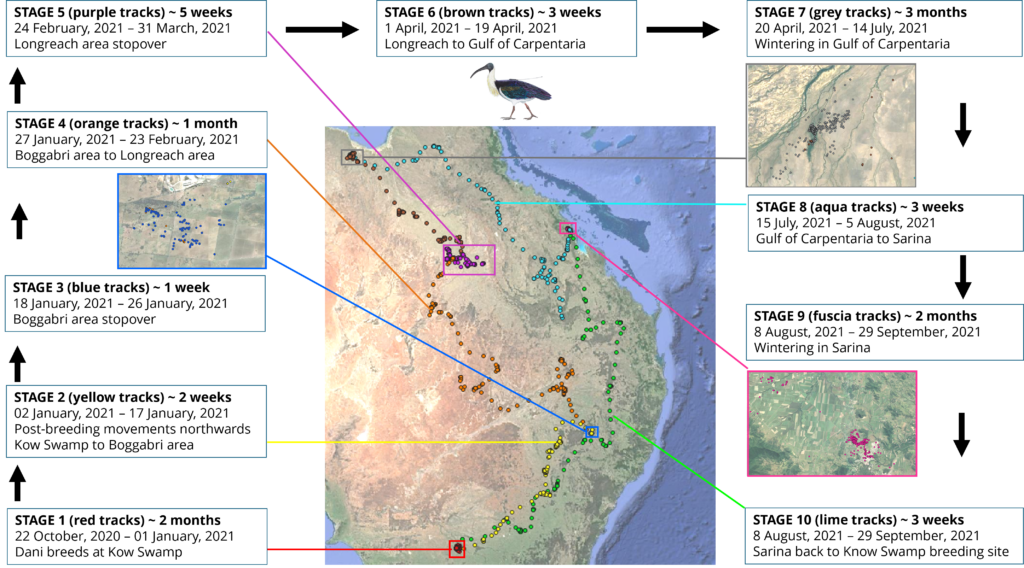

The below illustration of the movements of ‘Dani’, an adult straw-necked ibis, from 2020-2021 is a great example of nomadic behaviour. Dani bred in Kow Swamp in the summer of 2020 and then undertook a huge series of movements spanning half the Australian continent, before returning to Kow Swamp almost a year later to breed again. Some areas were visited only briefly while Dani stayed for months in others.

Nomadic movements of Dani the straw-necked ibis in 2020-2021.

Migration

Some waterbird species exhibit fully predictable annual migration every year of their adult lives. For example, coastal shorebirds like curlews and sandpipers move to breeding grounds in the northern hemisphere every austral winter and return to Australia every austral summer. Their movements occur at precisely the same time every year, sometimes down to the day!

None of the inland waterbird species or individuals that we have satellite-tracked have been classically migratory in this way throughout their lives. However, our research has revealed that individuals can exhibit behaviour that matches very closely with what we understand to be migratory movements, in some years. These individuals may move between the same breeding site and overwintering site using a similar route in different or successive years – but then move entirely nomadically in other years and not visit those sites at all.

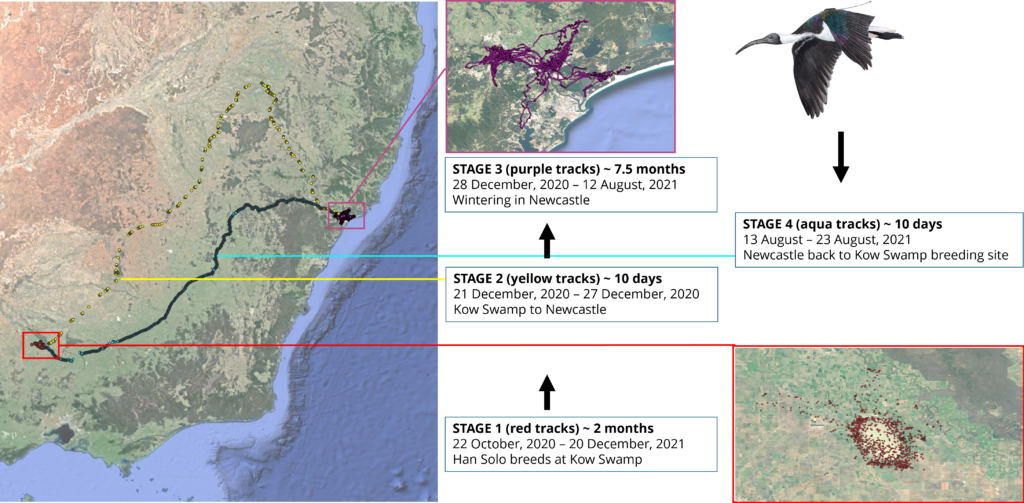

Meet Han Solo, a straw-necked ibis who, like Dani (see above) nested in Kow Swamp in the summer of 2020. Unlike Dani, after breeding in Kow Swamp Han Solo flew straight to Newcastle and then spent nearly 8 months there! Afterwards, he flew straight back to Kow Swamp to breed again. This is a great example of migratory behaviour.

Migratory movements of Han Solo the straw-necked ibis in 2020-2021.

Han Solo exhibited this type of migratory behaviour in multiple years but has also moved nomadically at times.

Without satellite tracking we would never be able to understand the movements of Australia’s inland waterbirds around the interior of this vast continent in such amazing detail.