Background

What is the weed problem?

African Boxthorn is a widespread and significant environmental and agricultural weed in regional Australia, and a Weed of National Significance (WoNS). Infestations are considered a major problem as the weed invades pastures, roadsides and reserves; displacing native vegetation, altering habitats and overrunning pastures and other areas. Dense stands are known to exclude most other species, impede stock movement and access to water, and harbour vermin (e.g. rabbits and starlings). It is also known to host a range of significant agricultural pests such as the Queensland fruit fly (Bactrocera tryoni).

African Boxthorn is widespread in coastal to semi-arid inland habitats, often occurring close to permanent or seasonal water sources. It is widespread in New South Wales, South Australia, Tasmania and Victoria, with restricted distributions in Queensland and Western Australia, and extremely restricted distributions in the Northern Territory.

Infestation of African boxthorn in a pasture in NSW.

How is the weed currently managed?

Control of African boxthorn infestations is difficult due to the presence of the weed across a range of landscapes, its role as important habitat in degraded sites, and destructive management techniques which are potentially unsuitable in culturally and ecologically valuable sites without careful planning. Conventional physical and chemical control measures are therefore considered inadequate to manage the threat from African Boxthorn, particularly on such broad scales, in regional settings where infestations may be difficult to access, and in sensitive natural environments.

For more details on the management of African boxthorn see:

African boxthorn – National best practice manual

Mechanical removal of African boxthorn (source: South Myall Landcare).

What can biocontrol offer to the weed’s management?

Biological control offers promise as a control method because it is non-destructive, cost effective and sustainable, with little chance of off-target damage, particularly suitable in culturally and ecologically sensitive areas. Few organisms are associated with African boxthorn in Australia, indicating it may have been “released” from natural enemies, which may hold promise to control the weed in the future. The relative taxonomic isolation of African Boxthorn in Australia, together with its negative impact profile, makes the species a suitable target for biological control.

A successful classical biological control program for African boxthorn would reduce the density of tickets, through defoliation of established bushes and/or reduction of new recruitment from seed. This could reduce the impact of the weed on associated vegetation and the need/frequency of other weed management tactics.

Flowering African boxthorn and fruit produced

Information on the fungal biocontrol agent, Puccinia rapipes

The biocontrol agent is a biotrophic rust fungus, Puccinia rapipes, that infects the leaves of African boxthorn. It was originally isolated from diseased boxthorn plants in South Africa. Through extensive host-specificity studies undertaken by the CSIRO, the fungus was shown to be highly specific to African boxthorn and other introduced, closely related Lycium species, and poses no danger to native Lycium species and other Australian species. In 2021, the fungus was approved for release into the Australian environment as a biocontrol agent to assist with the control of African boxthorn.

The full data set and comprehensive risk analysis are provided at this link: https://www.agriculture.gov.au/biosecurity-trade/policy/risk-analysis/biological-control-agents/risk-analyses/completed-risk-analyses/puccinia-rapipes

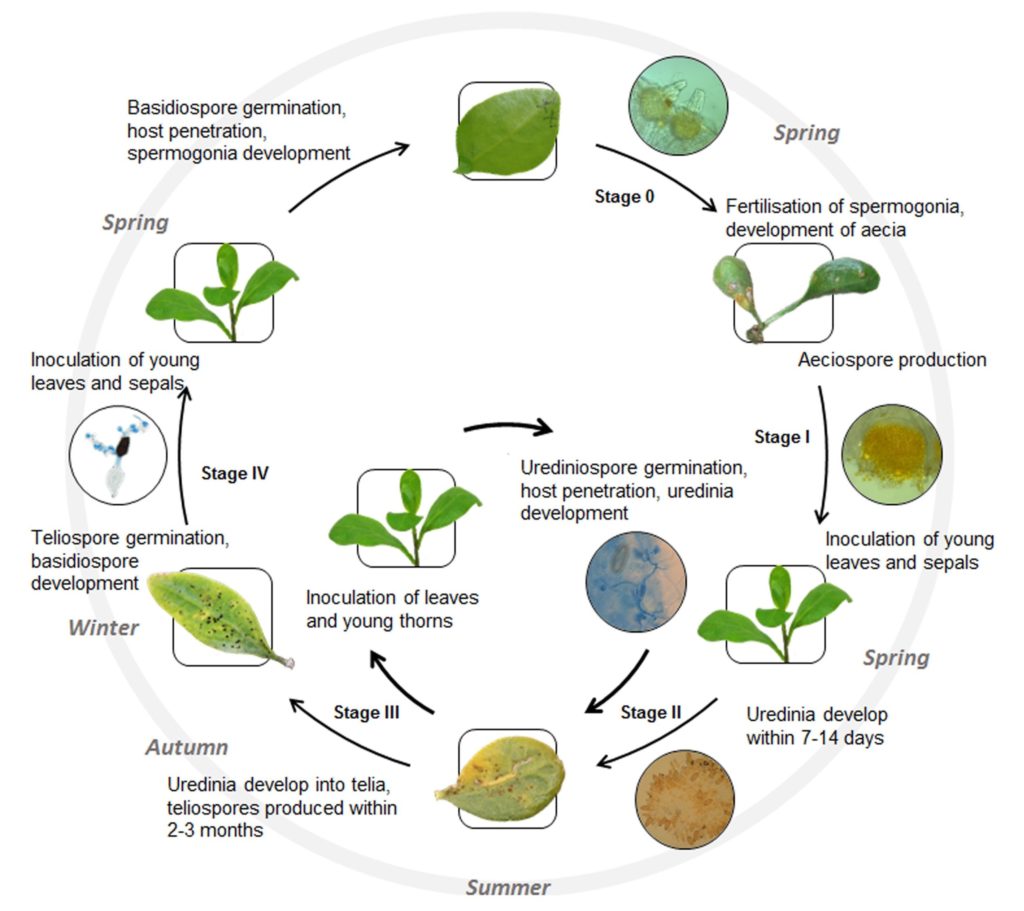

Illustrated life cycle of the rust fungus Puccinia rapipes on Lycium ferocissimum, with putative seasonal timeline.

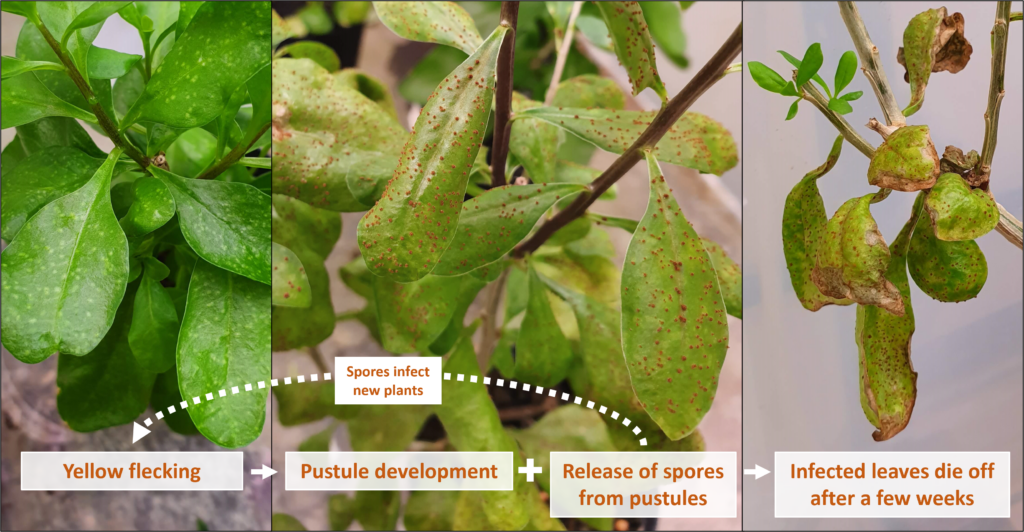

The rust fungus infects young leaves of African boxthorn, causing yellowing of the leaves followed by the development of pustules. The pustules produce fungal spores which are dispersed by wind. The spores land on the leaves of nearby African boxthorn plants and, under humid conditions, will germinate and infect new leaves. Infected leaves will die back over time. This may result in extensive defoliation of an individual plant if the fungus establishes widely and causes severe disease. Infection by the rust fungus can also disrupt the photosynthetic capacity of the plant, reducing overall plant growth and reproductive output.

Depiction of disease progression for the fungus on Puccinia rapipes

Releasing the biocontrol agent onto African boxthorn

The CSIRO will provide biocontrol participants with a biocontrol agent release kit that contains one or more vials of rust fungal spores. To apply the fungus to African boxthorn plants, participants will mix the dried spores with TWEEN 80 and water in a plastic spray bottle provided. This solution of spores and water will then be misted onto the leaves of the boxthorn plants in the late afternoon, and the treated stem covered with a plastic bag overnight. The fungal spores will germinate in this humid microenvironment and infect the leaves of healthy plants. The plastic bag will then be removed the following morning to prevent the fungus from being killed be elevated temperatures inside the bag when exposed to daylight.

Typical symptoms of infected boxthorn leaves and fruit in the field.

FAQs

What support is provided to participants in the African boxthorn biocontrol program?

CSIRO is Australia’s national science agency and leads the national weed biocontrol pipeline program. While CSIRO does not provide on-ground weed control services, it undertakes strategic research to develop and implement biocontrol programs that move approved agents from the laboratory into the Australian environment to reduce weed threats over time.

All CSIRO biocontrol programs are collaborative. CSIRO does not fund weed control directly. Instead, mass-release programs are delivered in partnership with stakeholders who contribute their own resources. This may include landholders releasing biocontrol agents on their properties or community groups undertaking releases as part of their volunteer activities.

To support these efforts, CSIRO provides:

- Biocontrol agent release kits free of charge,

- Training materials and online resources,

- Access to dedicated staff who can help design release programs tailored to local needs,

- Workshops and field demonstrations,

- Presentations of results at conferences and community forums.

We welcome expressions of interest and are happy to discuss how we can partner with you to deliver the project in your region.

How is the biocontrol fungus provided to participants, and are there limits on availability?

CSIRO maintains live cultures of the rust fungus Puccinia rapipes at its pathogen laboratories in Canberra and Floreat, WA. These cultures are carefully managed to ensure they remain healthy and uncontaminated for safe release into the Australian environment. We are currently establishing mass-rearing workflows and operational facilities to support national distribution of the fungus. Our goal is to deliver the fungus to at least 400 release sites across Australia over the next three years. However, this process takes time. Participants should expect a lead time of approximately three months from registration to delivery.

Release timing is coordinated to align with seasonal conditions that best support fungal establishment (typically autumn and early spring). We do not recommend releases during summer, as high temperatures are not conducive to successful establishment. Instead, summer is used for co-design and planning with participants to ensure each release is tailored to local conditions and needs. CSIRO works collaboratively with each participant to determine the quantity of fungus required based on the number of sites and the density of African boxthorn at each location. We also coordinate the timing of releases to match both fungus availability and local climate suitability.

While we welcome all expressions of interest to participate in the program, releases must be delivered equitably across stakeholder groups and geographic regions to ensure coverage of the full distribution of African boxthorn in Australia. On some occasions, we may prioritise distribution to certain areas over others based on strategic needs, which may result in longer wait times for some participants. Community-led releases may begin as early as October 2025, provided conditions are favourable. We anticipate strong interest in the program and will endeavour to meet demand through careful planning and engagement. Participants will be supported with training materials, release kits, and access to staff who can help design release strategies tailored to local needs.

What quantity of the biocontrol agent will I receive for release into the environment?

Registered participants will receive via post a “biocontrol agent release kit”. Each biocontrol agent release kit will contain a plastic vial of dried spores collected from pustules produced by the rust fungus. This vial of spores can be used to make a release at one site on a small number of African boxthorn plants. As those plants become infected, the fungus develops pustules which produce spores. Those spores will in turn naturally spread to nearby plants via wind or water and continue the spread of the fungus.

CSIRO staff will work with you to determine the total number of release kits provided, depending on your capacity/interest to release the fungus in your local region. To increase the chances of successful establishment of the fungus, we encourage participants to release the fungus at two points with two separate vials of spores, each separated by at least 200 m. Participants are welcome to request more release kits, but supply is dependent on stock availability.

Is it safe to release the biocontrol agent into the Australian environment?

In 2017, CSIRO began rigorous evaluation of the risks that the fungus Puccinia rapipes could pose to non-target plants in Australia. Research focused on species within the family Solanaceae. This extensive host-specificity testing was performed in a quarantine facility and involved exposing African boxthorn and non-target plant species to the fungus under optimal conditions for infection. It was found that the fungus is highly specific to African boxthorn (Lycium ferocissimum) and Goji berries (L. barbarum, L. chinense and L. ruthenicum; of which the rust can be easily treated with fungicides already used by goji growers). Based on these research results and following a comprehensive risk assessment process and public consultation, the Federal Department of Agriculture, Water, and the Environment (DAWE) approved the release of the biocontrol agent into the Australian environment. The information package that supported the application to release the agent in Australia, which includes all results, can be found here: https://www.awe.gov.au/biosecurity-trade/policy/risk-analysis/biological-control-agents/risk-analyses/completed-risk-analyses/puccinia-rapipes

What effect will the biocontrol agent have on African boxthorn populations? How quickly does the fungus kill African boxthorn?

In the Australian environment, the fungus is not expected to kill African boxthorn. Provided that the biocontrol agent establishes widely and causes severe disease symptoms on African boxthorn, it is expected to reduce the reproductive output and vegetation growth of the weed in the long term. This will in turn reduce its invasion potential in various ecosystems, but will not eradicate it altogether.

How quickly will the fungus spread?

The rate of spread of the fungus will be ascertained by long term monitoring. It is expected that the fungus will spread from one plant to the next very slowly, but the rate of spread will accelerate once the overall abundance of the fungus builds up in the local African boxthorn population. Based on our knowledge of other successful biocontrol agents that have been released previously in Australia, broadscale spread of the fungus would be expected to take several years and will not occur within the first season of release. As such, ‘success’ in the short term for this research project is to first establish the presence of the fungus in the Australian environment.

Can use of the biocontrol agent replace herbicide application or other control methods?

Biocontrol may provide a sustainable, landscape-scale approach for African boxthorn management with no chance of off-target damage to crops or native vegetation. Given that the fungus will not kill African boxthorn altogether, it will complement but not replace the need for other control methods. However, widespread establishment and spread of the fungus may gradually reduce the quantity of chemical herbicide required to suppress weed populations.

What happens if I cannot detect the fungus after release? Has it failed?

It is important to note that the fungus will only infect African boxthorn at high severity under optimal conditions for growth and spread – that is, when warm and moist and the host African boxthorn plants are healthy and vigorous at early stages of growth. As such, we expect that the fungus will not establish in all instances. The fungal spores are delicate and require specific microclimate requirements for germination and infection. The fungus will only become widely established in the Australian environment after many years of sustained releases by various participants.

As such, participants are encouraged to release the fungus on multiple occasions where the initial releases may have failed.